|

It was mid-December, I hadn't started my Christmas

shopping and I'm not known for my spontaneity. But

when asked if I wanted to take a five-day charter

cruise of Southwest Florida, I surprised myself

by exclaiming, "Yes."

My Travel companions, Ken Quant and Melissa Suring,

who were cruising veterans, wrote out their Christmas

cards on the plane while I, a first-time charter

cruiser, frantically flipped through Claiborne Young's

Cruising Guide to Western Florida.

Apprehension took a backset to anticipation when

we stepped off the place in balmy Florida and drove

past palm trees, pink and turquoise houses decorated

with Christmas lights, and old oak trees covered

with Spanish moss. At the Marinatown Marina in North

Fort Myers, Vic and Barbara Hansen of Southwest

Florida Yachts welcomed us warmly.

A primrose path led us past the Spanish-style buildings

the surrounded the Burnt Stone Marina. I carefully

stepped out of the sidewinding path of a crab to

climb aboard Ocean Cabin, the Catalina 42 that would

be our home for the next few days.

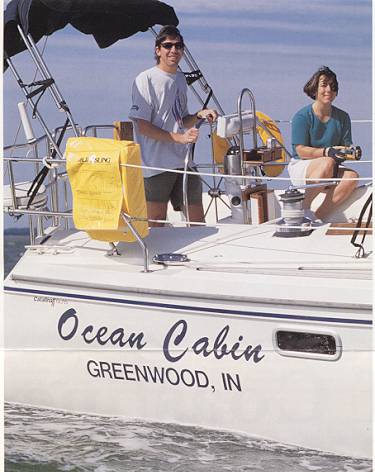

Ken Quant and the author enjoy

a sunny cruise in the playpen, a

protected, consistently deep area in Pine Island

Sound.

It was getting late in the afternoon. We quickly

stowed our groceries and slapped together peanut

butter sandwiches before preparing to sail the 10½

miles across Charlotte Harbor on our way to Gasparilla

Island.

Gray storm clouds loomed large behind us and then

mercifully headed north, spitting rain as we unfurled

the genoa in the 18-knot breeze.

Cormorants and pelicans glided evenly above the

water and then dropped from the sky like bombs.

I watched them from the deck as Ocean Cabin reached

across the bay.

"Dolphins," Ken shouted from the wheel. Melissa

and I rushed to the bow in time to witness three

dolphins, maybe four, leaping alongside us. They

were so close I could see the blow holes on their

smooth, gray bodies as they emerged, then disappeared

into the murky depths.

The wind calmed and we reached along at a lackadaisical

5 knots, navigating the marked path of the Intracoastal

Waterway to Gasparilla Island.

George, a blurry guy with a hearty laugh, guided

us into a small slip at Miller's Marina.

We were followed by a weathered looking man in

a weathered old aluminum cruiser, with the name,

something like Merriweather, faded on the transom.

His boat's engine had a bad smoker's cough and there

were clothespins hanging on its lifelines. "This

guy looks pretty salty," said George as he moved

to the other side of their pier to take his lines.

It was getting dark. At George's suggestion, we

followed candlelit brick pathways through downtown

Boca Grande, Gasparilla Island's only village. It

was mid-December, not yet tourist season, and the

locals were holding their Christmas festival. After

visiting the art galleries and shops, we bypassed

the much talked about Pink Elephant to have dinner

at the less conspicuous Mango Tree.

The sign said "Open" but it took three raps on

the screen door to rouse the restaurant staff, who

seemed to be savoring the last slow weeks before

the tourists would arrive. In the outdoor garden,

we ate fresh grouper with lime ginger sauce and

drank cold Heineken in the company of a gecko that

watched us sedately from the wall.

Returning to our cozy berths in the dark, I remembered

something my husband said to me before I left: "Don't

forget to look up." Sure enough, the big Florida

sky was pierced with starts.

When I awoke the next morning just before sunrise,

our salty neighbor was already sitting in his cockpit.

His name was John, and he was about to head back

on the Intracoastal to his Tallahassee home. Schools

of mullet slapped their tails on the water as we

shared his pot of coffee.

Motors puttered in the marina and men spoke in

one-word sentences, maneuvering the fishing boats

back in. Miller's Marina is famous for its tarpon

tournaments when the season peaks between April

and June, but the catches of the day were kingfish,

redfish, grouper and snook.

Grapefruit hung ripe and heavy in the trees as

we walked past old tin-roofed clapboard houses,

freshly painted in white, peach and yellow. Simple

and rustic, they somehow blended in to the newer

and larger homes with two cars and one cart in every

garage. These little carts or ballooned-tired bicycles

were the preferred way to travel, but we crossed

the island on foot, strolling slowly on Banyan Street.

Planted on either side of the street in 1914, the

great banyan trees had gregariously outstretched

their branches to create a shady canopy over the

street.

We passed Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Church. With

its wrought iron fence and stucco walls, it was

reminiscent of the Spanish explorers who established

a Catholic mission on the island in the 1500s.

Service was in session down the block at a white,

clapboard Baptist church, where organ music piped

out open windows.

As we walked singlefile along the concrete breakwater

to the beach, a line of sunbathing lizards disappeared,

one by one, behind the rocks. A freckled woman with

a pony-tail stood on the beach holding a fish pole.

Her companion, his pants rolled up to his knees,

was baiting his hook. The gray-haired couple cast

continuously into the white-green water at high

tide, "for anything that bites."

Meandering

past exotic and native plants, Ken Quant and

Melissa Suring

follow Useppa Island's botanical trail.

Slowly, the blue horizon became an ominous dark

gray. Ken broke the news that we wouldn't be anchoring

out that night.

Melissa and I rented a golf cart to sneak in a

visit to the island's two lighthouses. We visited

the tall, white skeletal structure that was built

in 1927 as a range marker for its predecessor, a

recently renovated 1890s cottage-style lighthouse

and its out buildings.

On the way back, the wind picked up and it started

to rain. We sat in the cockpit eating cheese and

crackers, listening to Billy Holiday until the bimini

began to leak. Under the marina's awning, we stood

with the marina crew and a man from Dusseldorf whose

shiny black-hulled ketch was docked two slips away

and watched it pour. I asked when it might let up.

George laughed, retrieving his cigar from the windowsill.

"This is Florida rain," he said.

So, we ate just-caught-this-morning stone crab

claws at the upstairs bar and grill, while George

and the bartender told tales of giant tarpon, aloof

bobcats and alligators that took up residence in

backyard swamps. But nobody knew the story of the

alligator that was stuffed and mounted on the opposite

wall. In the spirit of the moment, Ken invited George

to come sailing with us and I half-expected to find

him in the morning with his bag packed waiting on

the end of our pier.

It was a gray day with a big wind. We sailed,

on a broad reach, for the Tween Waters Marina. Almost

every channel marker along the way was residence

of an osprey and its young family.

Ken studied the chart and expressed his concern

about Ocean Cabin's five foot draft. We decided

not to risk going aground near the tight shoal Brian

Mowat of Miller's Marina had warned us about. Reluctantly,

we changed our course for South Seas Plantation

on North Captiva Island, a place that has been described

to us as Disneyland.

Sure enough, a triple-decker powerboat that could

have passed for a carnival ride was the first thing

I saw when we pulled into the slip. And when the

harbor master told Ken, "Your money's no good here"

we knew that he wasn't extending us a downhome Florida

welcome. The place had its own special credit card.

Walking past a manicured golf course, trolley cars

and boutiques, we slowly shed South Seas Plantation

to find North Captiva Island.

The gulf-side beach was a wide curvature of sand

bordered by sea grass that waved in the wind like

a horse's mane. A dark-haired woman sat on her ankles,

placing shells in a large wooden bowl.

It wasn't long before we joined her treasure hunt.

Walter, with his photographer's eye, found the most

interesting shells- a turkey food, a perfect conch

- which he passed to us as gifts. He dug a trench

in the sand to uncover coquina, tiny mussels that

look like agates. We watched as they opened their

shells, each kicking out a pale, pink foot to bury

itself back into the sand.

After dinner at the Mucky Duck, a friendly British

pub outside "the plantation," Melissa and I returned

to the beach by flashlight. The green waves broke,

hurling themselves evenly to shore where they foamed

and sizzled at our feet. They sounded like a chorus

of voices followed by an audience softly clapping.

Shivering in long pants, we sat on the expanse of

sand listening to the performance under the dark,

bright sky. Two stars fell and I made two wishes.

The next morning, I walked out to the farthest

point on the longest pier to wait for sunrise. A

fisherman rowed by in a wooden skiff, dangling a

net and a cigarette, which glowed softly in the

dark. Suddenly, a pelican flew at me. I stepped

back as he swooped up to take a seat on top of the

post I was leaning on. Together we watched pink

light climb the layered clouds into the sky.

It was beautiful, sunny day, perfect for cruising.

Melissa hoisted the main and I, a novice sailor,

fumbled with the jib. Ocean Cabin reached along

freely in the relatively deep water of Pine Island

Sound. We later learned that the locals call this

area the playpen.

The wind pushed us swiftly past Cayo Costa, a nature

preserve speckled with a white pelicans asleep in

the mangrove branches. A northwest wind pounded

and the tide was going out, taking with it my last

chance to experience gunkholing. It had only taken

a few days of cruising to accept that plans are

formed, dissolved and changed according to the weather

and the tide.

By special arrangement from Southwest Florida Yachts,

we were permitted to visit Useppa Island, a private

island known for its role as a training base during

the Bay of Pigs, for visits by presidents and for

its old money. According to the man at the main

lobby, there is nothing to do at Useppa, "unless

you like croquet." Instead, we followed the marked

botanical trail past eucalyptus plants, bamboo trees

and ficus trees. Melissa brushed her sleeve against

a branch, sending a flurry of zebra swallowtails

into the air.

We passed the Collier Inn, established by New York

entrepreneur Barron Collier, where a player piano

soullessly plinked out a Gershwin tune to an empty

room.

The old inn clearly wasn't open so we debated between

peanut butter sandwiches and a wet trip in the dinghy

to the famous restaurant across the Intacoastal.

Dollar bills cover the walls of Cabbage Key's

only restaurant, which is built on a Calusa Indian

shell mound. We pulled up to the dock just as the

sun was going down, tying our dinghy to the slip

marked 50-feet and over, and stretching our legs

as we admired the shaggy forest of cabbage palms.

I couldn't find the cheeseburger Jimmy Buffett

raved about on the dinner menu, so we sat at the

bar and ate fresh shrimp and blackened mahi-mahi

in paradise. The bartender, Mike Watts, told us

that the place is bustling at lunch when cruising

boats, the likes of which we'd seen at South Seas

Plantation, unloaded for lunch. It was late in the

day, two weeks before the tourist season, and we

were once again the only diners.

When we told them we had come from Useppa, there

was a long pause. "Is it true that they have a five-foot

chess board?" asked Mike. We told them all about

the boat with the United Nations flag Ken had seen,

the croquet course and the marked nature trail.

"We're not as sculpted here," said Jordan Smith,

a J/29 racer, who, at least until Key West Race

Week started, was Cabbage Key's official captain.

The night was overgrown with sailor chatter. Mike

was working 80-hours a week as a manager of a discount

clothing store. After his divorce 11 years ago,

he taught himself to sail. "It's a cheap way to

travel," he said. Recently, he married Donna, who

was our waitress. They live aboard a Catalina 13

at Cabbage Key for six months of the year. During

the other six months of the year, they cruise. Mike

wore a bracelet that said "live the dream," in block

letters. Ken wrote SAILING Magazine on a dollar

in black magic marker and Mike hung it in an honored

spot---next to the race car driver Dale Earnhardt's.

Entranced by their hospitality, we lost track of

time. It would have been a long, dark dinghy ride

back if Jordan hadn't been kind enough to offer

us a tow. He bought us to the channel marker outside

of Useppa. They sky was black, richer than old money,

and spangled with stars. A halo of phosphorescence

surrounded us as we motored back to Ocean Cabin.

On our last morning, the sunrise set the sky on

fire, but the temperature had dropped to a chilly

38 degrees. Cold crept inside the layers of fleece

we had piled on for the brisk ride back to the Burnt

Store Marina. Melissa found a patch of sun and stretched

out on the deck to soak it up. Walter curled up

in a blanket below. And I sat shivering in the cockpit

scanning the water. In my mind I summoned dolphins

to escort us on the journey home. rooms on a high-tech

campus.

Day is done for this elegant

little cat boat

anchored off

Useppa Island.

|